The Peak

Architect

- Niniek Febriany

- Reza Primardiantono

- Gilang Risky

Location

Amsterdam

Area

Status

Shortlist of 20

Year

After more than one million refugees flooded Europe in 2015, one question was on minds around the world: “What happens next?” Some who had made the difficult journey were sent back, making their trips all for nothing. Even for the hundreds of thousands who did arrive, many are still struggling to settle down in a country willing to take them in and are forced to move deeper into Europe.

In the Netherlands — a country to which nearly 60,000 people came in — thousands have no choice but to be cramped into the cities. Although many have been able to find temporary homes, there are many others who are still struggling to find one.

The city of Amsterdam is taking an active step in trying to resolve the refugee issue by specially investing two million euros in housing for refugees in the Netherlands. This money will be used as subsidies to encourage developers to turn private real estate into social housing. The city hopes that this financial support – in terms of subsidies of up to ten thousand euros per home – will help developers to take that step, while taking into account that the market pricing for a typical house in the Netherlands is approx. 200.000 euros.

The problem with typical landed houses is that they are very inefficient in terms of land use and economic value which is why social housing tends to look for land that costs as little as possible. That land is normally far away from opportunities for work, education, transportation and health that urban cities offer. Situating social housing residents far from cities lead to unsustainable commuting cost. In some cities, this has also tended to localize social housing in an impoverished urban sprawl, creating belts of resentment, social conflict and inequality within that area and amongst the city dwellers.

We envision that social housing should be seen as an investment and not as an expense. Thus, an inevitable outcome of this must lead to an increase of the initial subsidies value over time. This is logical given that when one purchases a house, one expects its value to increase. But the current view of buying social housing is more similar to buying electronic appliances than buying a house for habitation; the value decreases every single day. Hence, if the subsidy can add value over time, we could finally leave the never-ending social housing problem.

Videshiiya Studio aims to develop five strategies for increasing the value of social housing with a very tight subsidies budget.

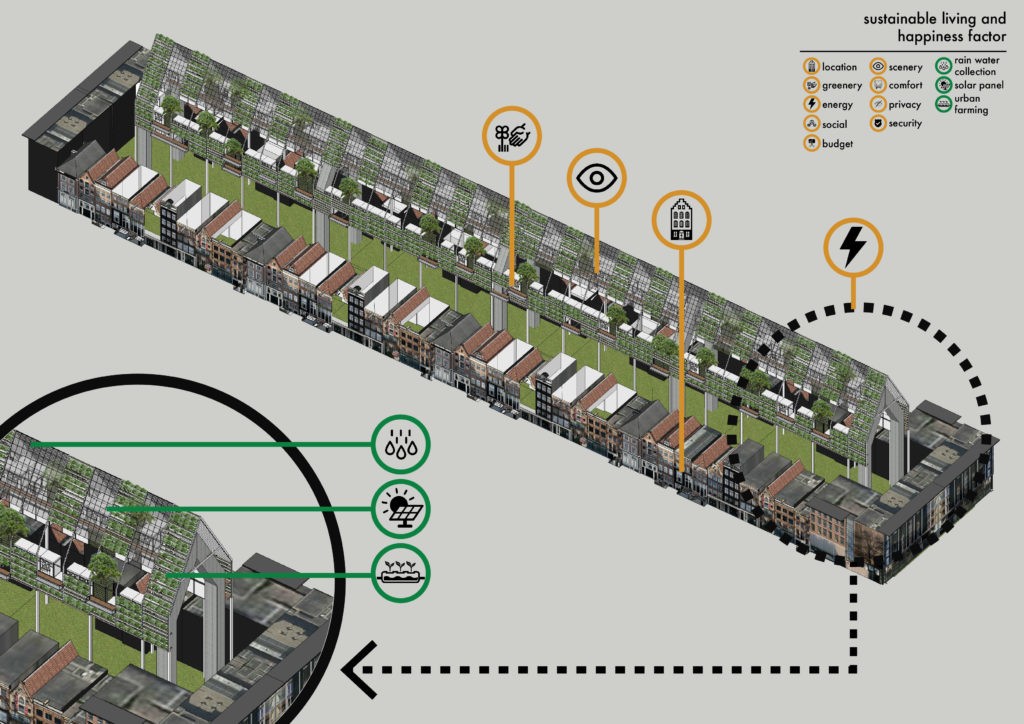

Location, location, location!

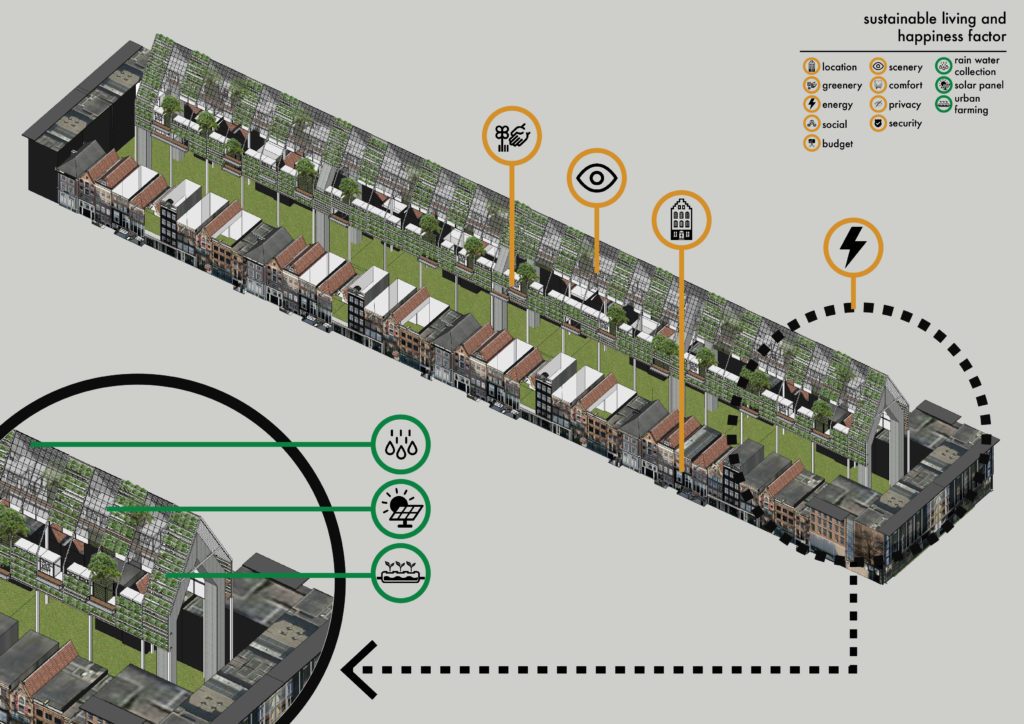

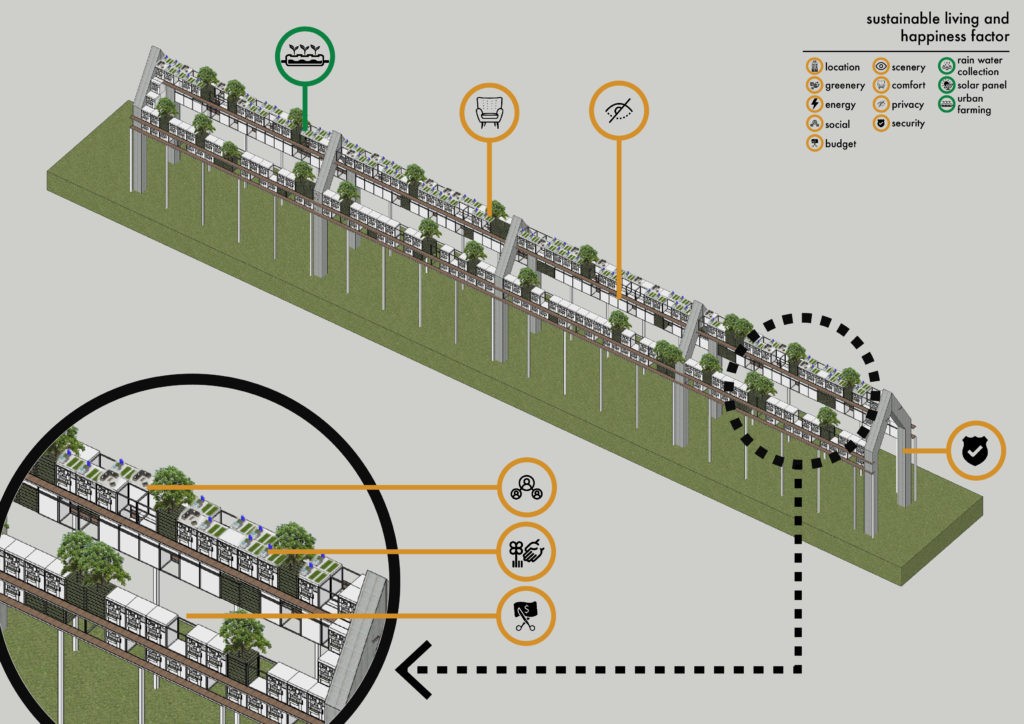

Our design is seeking to answer the best possible location in the city of Amsterdam without generating a further social, ecological, and land-use problem. The Peak project will be built over the inner-court of the residential block in the city of Amsterdam. This strategy is meant to maintain the network of opportunities that the city offers and therefore to strengthen the family economy; on the other hand, good location is the key to property value gain. In addition, each house will get an aerial view of the city and its canals, a rare privilege for social housing residents.

In order to be able to pay for the site, which is expensive due to its location, adequate density has to be achieved. The Peak is designed in a row of micro-houses (one-tenth of the typical middle-income house size) scheme to efficiently work and fit on the limited space.

Urban farming and social space

The introduction of community-run farming aims to improve community relationships, as well as health and well-being, reducing food cost, and offer an awareness of agriculture and food to The Peak’s residents. Along with the tremendous influx of the world’s population to urban areas, the need for fresh, safe, and affordable food has increased and it is envisioned that the urban farms would become important sources of food security for The Peak’s residents.

The energy-efficient urban farming can reduce the city’s carbon footprint by cutting the amount of transport that occurs when delivering food to the consumer. Also, these areas can act as carbon sinks offsetting some of the carbon accumulation that is innate in urban areas, where pavement and buildings outnumber plants.

Urban farming might also reduce racial and class disparities in access to healthy and fresh food. When urban farming leads to locally grown fresh produce sold at affordable prices, access to healthy food is not just available for those who live in wealthy areas, thereby leading to greater equity in rich and poor neighborhoods.

Improved access to food through urban farming can also help alleviate psycho-social stresses in poor communities, especially among residents who are still trying to find their place in a new society. Community members engaged in urban farming improve local knowledge about healthy ways to fulfill dietary needs. Thus, urban farming can help improve conditions in poor communities, where residents experience higher levels of stress due to a perceived lack of control over the quality of their lives.

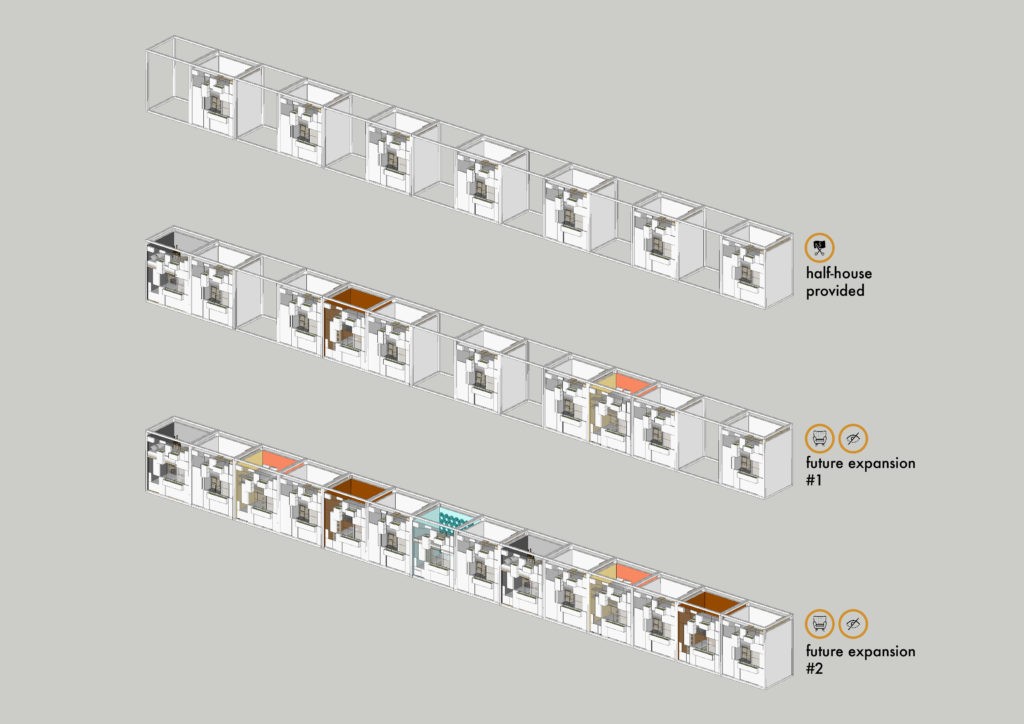

Future development

The extension of physical space (mainly because of the addition of family members) may prove to be an economic issue for a low-income family. By providing an extra lot of micro-house, a family could expand anytime without worries.

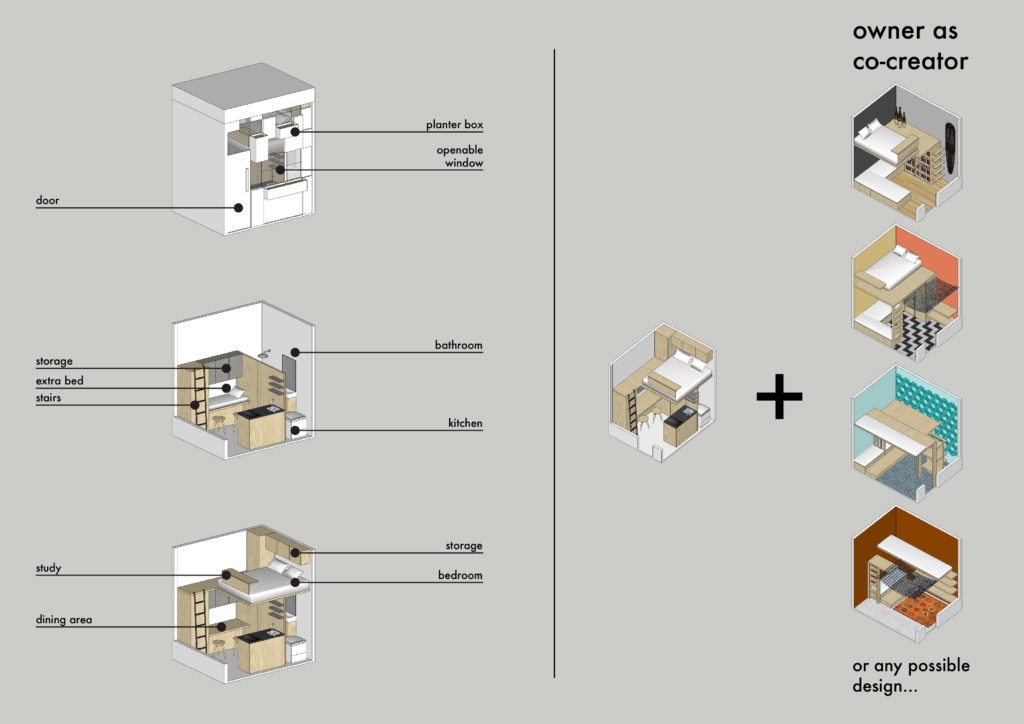

Half-house, half-budget

When the initial subsidy is enough for just half of the micro-house, the challenge is, which half should be built? We would choose to build the basic needs; such as kitchen, bathroom, bedroom, and the whole micro-house structure that will be economically challenging to achieve.

The low-income and immigrant family might not be able to afford a “good” house, but why should they only be given half a “good” house, instead of a poorly finished house? Social housing should not be a static unit that is packaged and handed over to people. Rather, housing should be considered as an ongoing project wherein residents are its co-creators.

They would turn the component parts into suitable housing, on their own terms. The family contributes their labour and building materials to finish the house. In the end, they own what they build. It is with this sense of ownership and belonging to something that requires a community effort that will spur the residents to take up their part in improving the community, and let them invest in and improve their very own homes.

‘Invisible Architecture’

Residents at their own time would expand into the adjacent empty space. In the houses designed and constructed by the resident, they will pay a close attention as to how they wish to live, ascertain what their needs are and which are then refined within the design process, which will enliven their homes. The ‘invisible architecture’ concept allows us to imagine houses as being shaped according to the lives we have to live, as opposed to imagining our lives being shaped by the houses we live in.

Within the vernacular architecture tradition, the direct involvement of people in the design and construction of their homes are literally powered by, and filled with, the vitality of their own lives. In comparison, when a house is designed and constructed by a stranger, such a romance may not emerge.